The Politics of Dress

Inside the Mind and Atelier of the French Collective Études

- Interview: Jina Khayyer

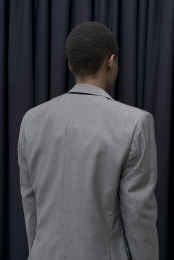

- Photography: Andrzej Steinbach

Études is a collective of six Frenchmen who grew up as neighbours in Grenoble. A true boys club—raised in the nineties and connected through their love of graffiti. Aurélien Arbet, Jérémie Egry, Nicolas Poillot, José Lamali, Antoine Belekian, and Marc Bothorel identify Études as a brand for “contemporary men.” They coalesce between multiple creative disciplines, from accessible clothing to a recently established publishing house. Collaborating with German artist Andrzej Steinbach, Études is debuting a political image-series: a special edition hoodie, t-shirt, and long-sleeve tee, each branded with the Flag of Europe, exclusively created for SSENSE. Although Études’ creative director, Jérémie Egry, says that the founding idea of using the European Flag was not planned as a political act, the collaboration with Steinbach addresses one of the most relevant topics of our time: social racism. Études decided to embrace the topicality.

Jina Khayyer

Jérémie Egry (JE), Nicolas Poillot (NP)

Your image-concept is super political: you refer to a scene in an American court, where Black Rights activist Bobby Rush is taking off his suit and covering his head with a hoodie in memory of Trayvon Martin, an African American boy, who was killed because of a hoodie wrongfully interpreted to be threatening. What about this inspired you to begin this collaborative project?

JE: The idea and images for this collaboration were developed together with Andrzej Steinbach. We chose Andrzej because he uses iconic fashion codes, but is also able to talk about political topics. Andrzej has a great eye and makes connections between someone’s personality and what this person wears. Everything you put on yourself is a political act. So today, in places like the States, if you’re black and you put on a hoodie, you can be killed by the police. We don’t want to live in a racist society, so we try to do our contribution to create awareness. But we don’t want to be moralistic either. Some people are not going to see the reference. But they will still see a strong image.

Have you ever been a victim of social racism yourself?

NP: I never feel it myself, but my girlfriend is black, so I feel it through her. It’s humiliating. Racism is a question of education. Thanks to my mother I was raised not to judge anyone, not to feel entitled, not to feel superior.

Social racism is also a question of identification. What do you identify as?

NP: I was born in France, but I feel more European than French. In fact, I’m even more comfortable to say I’m a European than to say I’m French.

What does it mean to be European today?

JE: We were born when the borders between every country in Europe still existed. It was beautiful to grow up and see how borders have been systematically suspended. It’s a great thing to be European. We’re really proud to be from Europe. But we are also very concerned. How can we keep the borders open and prevent the building of new fences and walls?

Is that why you decided to use the flag of Europe as a print?

NP: Yes and no. We did it when we realized that we are identifying as European and not as French. As a way of celebrating Europe, long before the hysteria of closing borders came up. Now it is political, and that’s good. The personal is always political, isn’t it?

That’s a political argument of the student and feminist movement from the late 1960s.

JE: We are unfortunately going back in time and have to now fight again for the same issues our parents fought for. Which is really ironic, seeing as our parents’ generation is now becoming more and more conservative again.

Is it the role of a designer to be political?

JE: It is the role of a human being to be political. If the designer identifies as a human being, then yes, it’s his role to be political. Fashion gives you great opportunities to raise your voice. Sure, when you work in fashion and you’re living off of capitalism, it can be a conflict. You don’t want to be a hypocrite. And you don’t want people to be depressed when they come into your store. But you also don’t want to throw your values overboard, just to sell a product.

On your website, you say that you are producing contemporary men's fashion. What makes Études pieces contemporary?

JE: Our references are from the present. In our work we are nostalgic, we want to talk about the now. We're sensitive to what's around us. What can you observe while leaving your house, taking the metro, and walking from the train station to your work, for example? And how can you connect these observations and experience to your work? Or translate them into a product? I think it's important for any creative person to be connected with la vie quotidien, the daily life.

What does masculinity mean today? It seems to be a major fixation of your collective.

JE: No, not really. Yes, we're men. And yes, we design clothes for men, but we don't really care about it. We don't think: Oh, it's men's clothes. Obviously there's a masculinity code. But that doesn't really interest us. We're more interested in what we want to say or explore, rather than thinking about a gender. Also we don't like to interpret too much into a piece of fabric. One goal of Études is to stop stereotypical thinking. The only codes we are interested in are the codes of modern society. And when it comes to gender, to use the modern society is gender fluid.

Études has six heads. Although each one of you is responsible for a separate division, it’s still six final opinions. Do you follow any hierarchy?

NP: No. We’ve always worked as a team since the beginning. We naturally chose to be a collective because we like to share our energy.

Do you also have a collective vision?

JE: Yes. Our goal with Études is to propose something creative but accessible.

Why did you choose Paris as a headquarters?

JE: That’s a good question. We just recently asked ourselves that, as none of us is from Paris originally. Throughout our youth we took advantage of the open borders and lived all over Europe. We are all graffiti artists, so we just went wherever we could find white walls and an empty couch. We decided to come back to France and move to Paris when we created Études. It was an experiment—we never liked the idea of Paris. But we’re happy about it. In the past few years the city has changed a lot for the better. Even if the last two years have been very traumatic, it’s good for Paris to get tough. Difficulties give you an energy that are good for creation.

- Interview: Jina Khayyer

- Photography: Andrzej Steinbach